what happened to esso building 7720 york road towson md

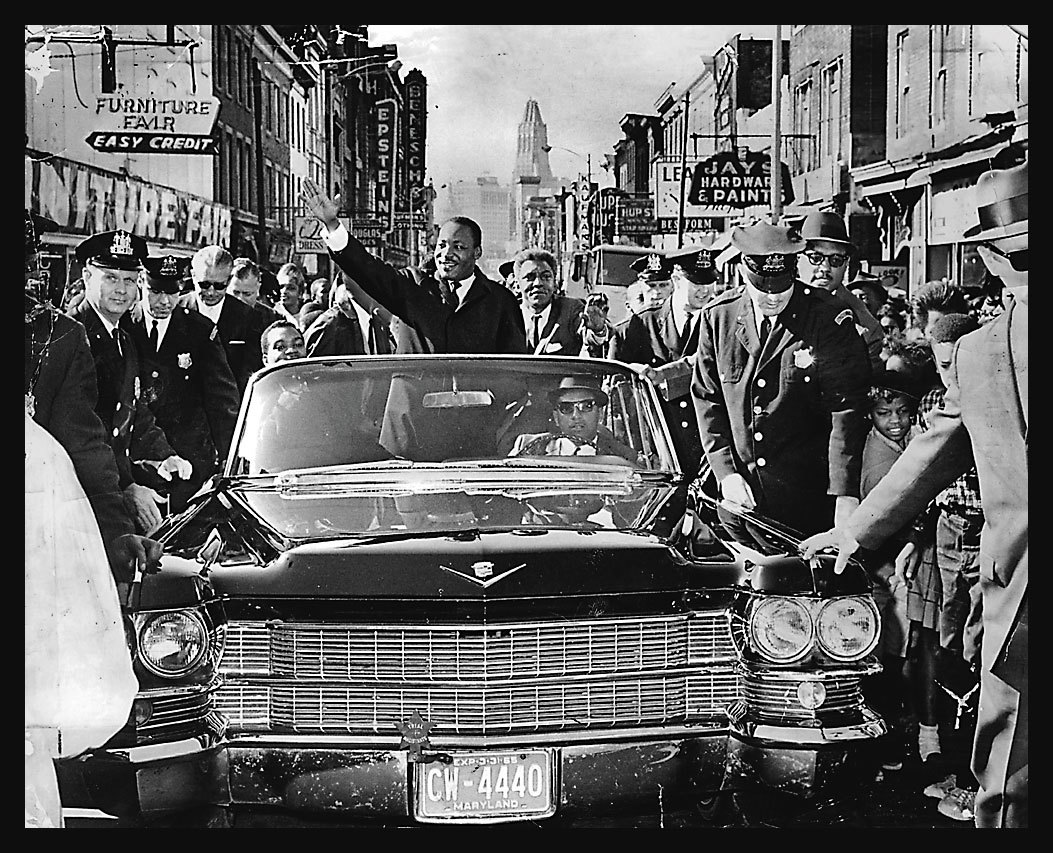

The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther Rex Jr., greets admirers on a motorcade bout up Northward Gay Street on October 31, 1964.

he morning time following Martin Luther Male monarch'southward murder in Memphis, Dick Basoco found himself heading to the Sunpapers' Calvert Street offices in an elevator alongside publisher Bill Schmick. "By that time, Washington had already broken out," recalls Basoco, this magazine'south former COO and executive editor, so a reporter for The Sun. "And let me preface this by saying Bill Schmick was as practiced, as decent, and every bit caring a human as you could promise to find publishing a newspaper in a big city. Merely his engagement with the urban center was coming to work, luncheon or dinner and drinks at the Maryland Order, which was all-white, then going back dwelling house up I-83.

he morning time following Martin Luther Male monarch'southward murder in Memphis, Dick Basoco found himself heading to the Sunpapers' Calvert Street offices in an elevator alongside publisher Bill Schmick. "By that time, Washington had already broken out," recalls Basoco, this magazine'south former COO and executive editor, so a reporter for The Sun. "And let me preface this by saying Bill Schmick was as practiced, as decent, and every bit caring a human as you could promise to find publishing a newspaper in a big city. Merely his engagement with the urban center was coming to work, luncheon or dinner and drinks at the Maryland Order, which was all-white, then going back dwelling house up I-83.

"I'll never forget what he said, 'Our negroes aren't going to practise that.'

"It wasn't the use of 'our negroes' that stood out to me," Basoco continues. "I didn't try to parse whether he believed that blacks in Baltimore were more than civilized, or more cowed, than those in D.C. It was how out of touch he was. I found it astonishing. The full general feeling in the urban center was 1 of dismay, and if you lot believed in what King stood for, a deep sense of loss."

King was no mere television presence in Baltimore. He had visited the city at to the lowest degree eight times for public addresses, including twice in 1966. In fact, Rex had canceled a scheduled appearance in Baltimore in March of '68 to join striking sanitation workers in Memphis.

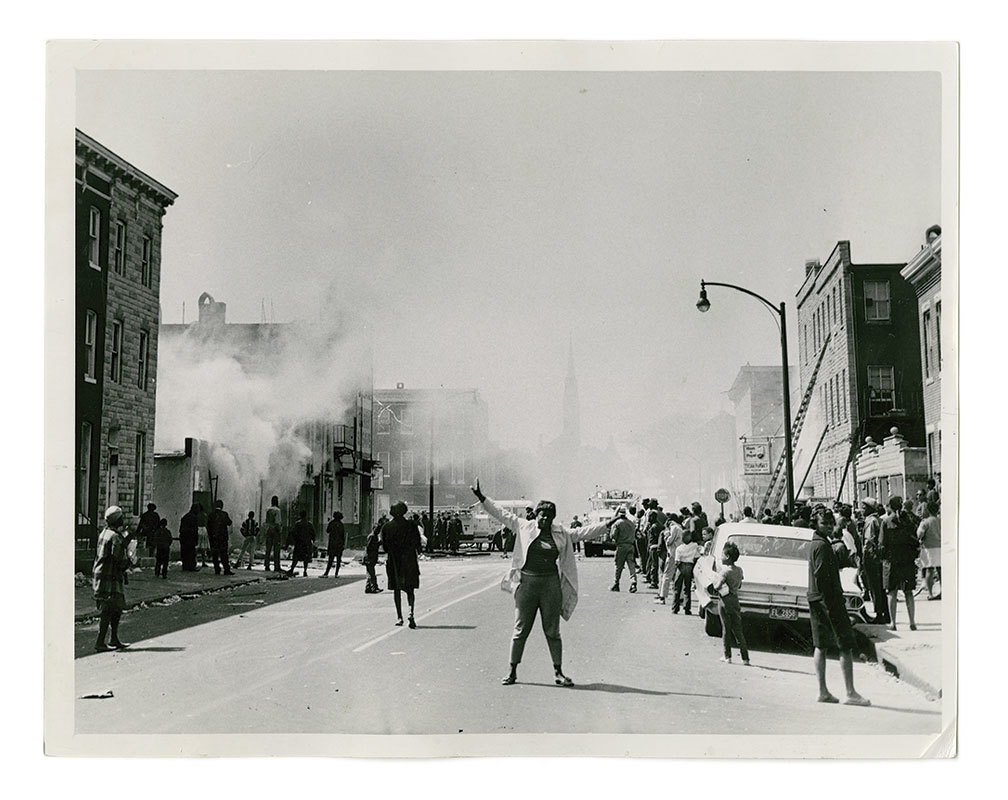

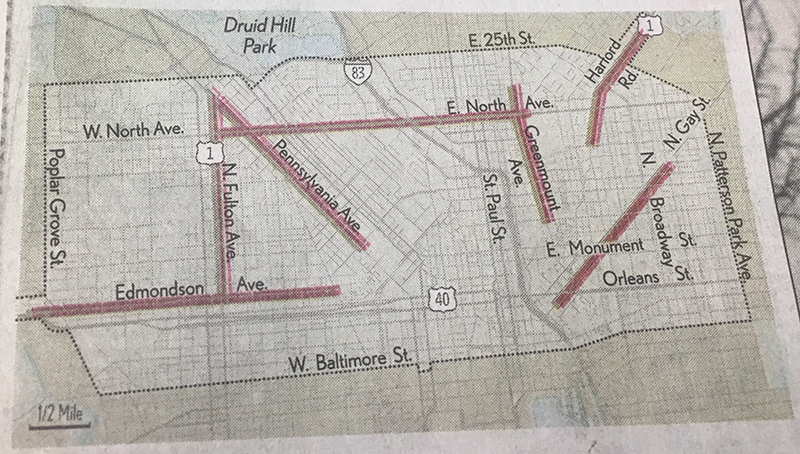

At noon on Saturday, April half-dozen, two days afterward King was assassinated, with his shooter still at-big, 300 people attend a peaceful commemorative service in W Baltimore. Later, a second, interdenominational service is held. Then, suddenly, at v p.m., the first reports of smashed windows and crowds gathering in the 400 block of North Gay Street are called in to constabulary. An hour after, the get-go report of looting in the E Baltimore commercial corridor—at a dry cleaner's on Gay and Monument streets—comes in. By 6:xxx p.m., two Gay Street furniture stores are in flames, and all off-duty policemen are ordered to work. At 8 p.thou., Gov. Spiro Agnew declares a country of emergency in Baltimore. At 9:15, with assurances from the Baltimore Police Department, Agnew declares the situation is under control. But even equally he makes these remarks, an A&P on the 1400 cake of N. Milton Street is beingness looted and torched along with three adjacent stores.

Meanwhile, Robert Bradby, a 21-year-erstwhile steelworker, has tossed a Molotov cocktail into Gabriel'south Spaghetti House on E Federal Street, which volition lead to the expiry of Louis Albrecht, a 58-year-onetime white resident. Bradby later volition say he'd been angered by shots that rang out almost him, believing they had come from the restaurant. Around the corner, the torso of black xviii-year-old William Harrison is discovered. At 10 p.m., Agnew reverses form and commits the National Guard. He bans the sale of liquor, firearms, and gasoline in the city and surrounding counties and puts in identify an xi p.m. to vi a.m. curfew. Over the side by side three days, Baltimore would witness unprecedented upheaval. Of the more than 100 cities across the country that experienced disturbances after Male monarch'south death, Baltimore topped the list in harm forth with Washington, D.C. The tally: six dead; more than 700 people injured; five,500 arrested—filling city jails and the borough eye with detainees—more than ane,000 businesses looted, damaged, and/or destroyed by fire; and $98 million in holding damages in today's dollars. "Information technology was horrible," Rev. Marion Bascom, a prominent civil rights leader, said later. "Yous could smell smoke anywhere in Baltimore City."

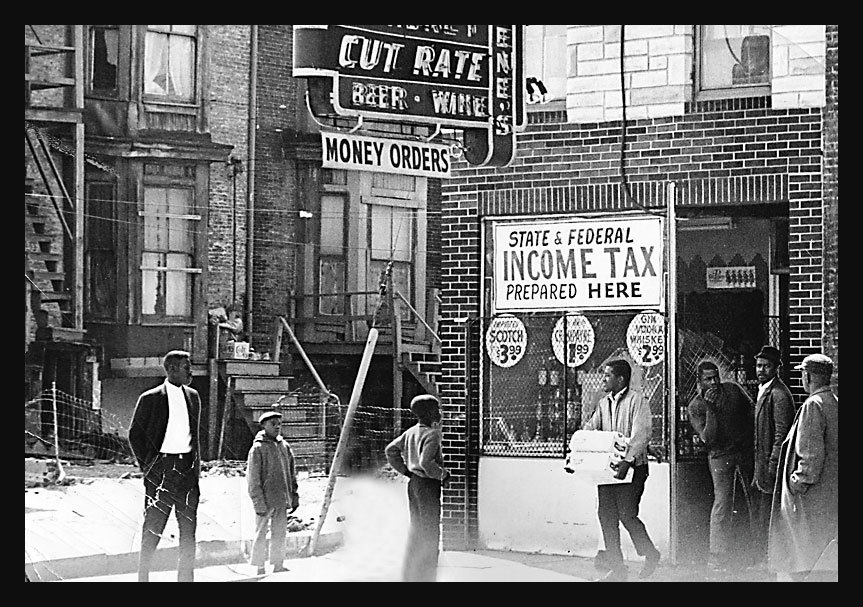

In a way, the metropolis had been a pressure cooker for decades due to its racial divide. Then the 6th-largest city in the country, Baltimore's public and private segregation remained thoroughly ingrained, along with an indelible Southern ethos. White Baltimoreans cheered blackness Baltimore Colts such as Lenny Moore and Jim Parker at Memorial Stadium, but they did not socialize with black Baltimoreans any more than the Colts' white players socialized with their black teammates.

At the same time, Baltimore was also a blue-neckband boondocks, and by 1968 information technology was already hemorrhaging jobs, residents, and its revenue enhancement base to the suburbs. The combination provided a double whammy to the urban center's mushrooming black population. Enabled by an array of discriminatory local, state, and federal policies and practices, surrounding Baltimore County was booming, further tightening the knot of poverty around the inner city. From World War Two until 1968, the urban center's population remained stable, but its racial makeup had shifted dramatically. More than than 700,000 whites lived in Baltimore in 1950; a generation later, fewer than 500,000 did. Meanwhile, Baltimore County's population exploded from less than 250,000 in 1950 to more than 600,000 by 1970 while the number of blackness residents remained static at 20,000. None of this was simply market-driven phenomena.

The primal piece of legislation was a 1948 amendment introduced by Baltimore County officials to Maryland's constitution substantially outlawing further expansion past the urban center, which in the past had annexed land as residents and businesses spread outward. (Baltimore remains a rare big city not part of a broader canton jurisdiction, hamstringing tax revenue and the potential to desegregate schools and neighborhoods.) From Globe State of war II to 1968, jobs in the city rose by eleven percentage; in the county they rose past 245 percent. Despite ceremonious rights victories, blacks were not gaining economically. "You lot can't help only remember there was a mix of raised hopes and unmet expectations in black neighborhoods," says Peter Levy, author of The Great Insurgence: Race Riots in Urban America during the 1960s.

The aftermath of King'due south death and subsequent riots in Baltimore were both profound and personal. One-third of businesses destroyed in rioting never reopened, leaving gaping holes in the Gay Street and Pennsylvania Artery corridors that remain to this day.

On the other hand, for a 19-twelvemonth-quondam Kweisi Mfume, who was arrested during the anarchism for breaking curfew, King's death and the uprising provided a starting betoken. By take a chance, Mfume, who had lost his mother years earlier and was working 3 jobs to try to support his family, came across civil rights veteran Parren Mitchell at the burned-out corner of Robert and Division streets in the weeks after the disturbance. Mitchell was running for Congress. "He was trying to organize people, and I said something like—'Man, what are doing you hither? This is my corner'—and shot him an intimidating wait. At to the lowest degree I thought it was intimidating," Mfume recounts with a express joy. Mitchell but stared back and extended his hand. "He was not intimidated, and his look communicated he knew what I was going through."

Mfume ended up volunteering for Mitchell's campaign. Mitchell lost that race, but so won in 1970, condign the first African American from a Southern state elected to Congress since Reconstruction. Mfume, of form, would later win Mitchell'south former seat and go on to atomic number 82 the NAACP. "I felt heartbroken and helpless when Martin Luther Male monarch was killed," Mfume says. "All the air went out of me, and when you went out into the street you could see everybody felt the same way. And people were angry. Before you knew information technology, someone was throwing a trashcan through a window. Just that was likewise the fourth dimension I decided I needed to do something."

When University of Maryland police force professor Larry Gibson got the news of King's decease, he was clerking for a federal judge—the first African American to do and then in Maryland. "I had accepted an offer to join Venable, Baetjer & Howard, which was the biggest white institution practice in the city," Gibson says. "I turned it down subsequently his death and called the biggest blackness law business firm in the city and I got involved in politics."

Gibson would organize the entrada of Guess Joseph Howard, who won a seat on Supreme Bench of Baltimore City that November, helping elect the first African American to a citywide office. Gibson would later direct the campaigns of Kurt Schmoke, who became Baltimore'southward first elected black mayor in 1987.

"You lot can't assist simply think there was a mix of raised hopes and unmet expectations in black Neighborhoods."

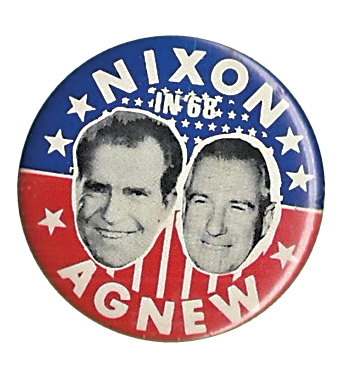

The most worrisome political effect of Baltimore's 1968 riots would bear witness to exist the meteoric ascent of Agnew into national prominence. On April 11, before long after the rioting had ended, the Maryland governor chosen 80 Baltimore black leaders to a downtown meeting that was, in truth, a setup for a scapegoating printing conference. With members of the state police and National Baby-sit in tow, Agnew castigated the city's black pastors and political activists for the violence. Most in attendance walked out on Agnew, who scolded them for being afraid to stand up to black radicals for fear of being called "Uncle Toms." Not only was Agnew'southward vitriol supported past many white Marylanders (who Agnew said sent thousands of telegrams praising him for his dressing down of Baltimore's black leaders), it caught the attention of Pat Buchanan, counselor to presidential candidate Richard Nixon.

With his hardliner bonafides assured, Agnew earned segregationist S Carolina Sen. Strom Thurmond'south seal of approval as Nixon'due south running mate. Agnew, the palatable, suburban alternative to George Wallace, quickly emerged as the heavy in Nixon's law-and-gild campaign and Southern Strategy, which continues to hold sway in the GOP to this mean solar day. Almost immediately, the Nixon Administration ditched Lyndon Johnson's State of war on Poverty for a war on drugs that specifically targeted African Americans and has yet to come to end.

A half-century ago, the National Advisory Committee on Civil Disorders described white America as "deeply implicated" in the poverty of black Americans. In February, a written report from the Economical Policy Institute found blacks have made strides in educational attainment and family wealth, only in pregnant respects have fabricated picayune progress, really losing ground relative to whites, and, in a few cases, even to African Americans in 1968.

Black unemployment is up slightly from 50 years ago, and homeownership rates remain unchanged. The share of incarcerated African Americans has tripled—to more than six times the white incarceration rate.

"People naturally want to be hopeful, I empathize that," says Paul Coates, who joined the Black Panther Party in Baltimore in 1970 and has been the publisher of Black Classic Printing for the by iv decades. "And I keep watching for signs that the land of this country is getting ameliorate, in terms of race. But I don't know that I can offer hope. It is meliorate for some. The nearly encouraging thing I see when I reverberate on 1968 and then the marches post-obit the death of Freddie Greyness is that the protests after Freddie Gray looked more like a movement of blackness and white people.

"But overall, I don't see that things are getting better in America, non for black people, or more broadly, those in poverty. Non nonetheless."

Ed Mattson

Baltimore police sergeant

I was assigned to the tactical squad—what had been the riot team—at the old Southwestern District Police Station at Pratt and Calhoun. Information technology was a citywide unit, and I supervised about 15 guys. The day after Martin Luther Rex'due south assassination, April 5, was quiet, only you could feel it coming. There were pockets of resistance. On the sixth, a bespeak 13—officer needs assist—came in at near four p.yard. from Gay Street, the 1200 or 1300 cake, if I remember. It was total-blown when we got there. People were busting bottles, throwing bottles at us, all that kind of stuff. Officers were battling people. A warehouse went up in flames. The next 2 days, it blossomed. It wasn't anything organized. Just helter-skelter. People throwing Coke bottles filled with gasoline and a wick. Pure anger.

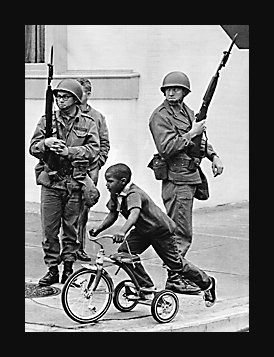

In all honesty, the National Guard, land police force, and federal troops didn't exercise much. The Baltimore Police Section kept things from spreading further. Everything took place substantially in a rectangle in the inner metropolis. We'd go a report of a mob forming, and we'd run to information technology, suspension it up, and arrest everybody. We fabricated thousands of arrests. Filled the jails and borough eye. I didn't go home for 3 days.

It had started to alter, but probably 98 percent of the patrol officers were white males. Afterward nosotros were told to stand downward a calendar week and a half subsequently, an undercurrent remained. In that location were pockets of resistance and pocket-size riots over the adjacent few years. People forget that. The tension [between black neighborhoods and the police department] was e'er there afterward that.

Jewell Chambers

Baltimore Afro-American reporter

I had been involved [with the ceremonious rights movement] prior to '68. I was arrested in 1960 for sitting-in so at Morgan State in 1962 when Morgan took over the Northwood Shopping Center. You had Hochschild's [Hochschild Kohn'southward department shop] that had a tearoom in which you couldn't eat; you lot had a theater that ran "B" films, the Northwood Theater, to which you couldn't become.

The idea of a riot by 1968 was not new. By this fourth dimension you had gone through Detroit, Watts. I would say things were . . . tense is non the word . . . I think the thought was that things were changing.

I was 25. I had taken [a friend's] female parent food shopping at Mondawmin Mall, and the observe went through that Male monarch had been shot. I went home to heed to the radio and mind to the telly and find out what had happened. When they began to play the [speech], "I've been to the mountaintop, I may not be there with you," that merely sent cold chills downward you.

I was the only woman on city desk. This has stuck with me forever—I was upwards on Thomas Artery simply below North [Artery], the black section—centre, lower-middle class. There is a corner bar, and they had already trashed information technology. So I'yard in at that place and there'southward this blackness guy telling people what yous tin accept . . . merely the good stuff is gone. And he'due south sitting there and he's maxim, "And don't be lighting . . . don't be lighting no matches 'crusade I live upstairs. Take whatsoever is here, merely thing here is cheap . . . but don't be lighting." He probably saved it. They didn't light whatsoever matches.

"And the whole cake was in smoke and flames. That was the betoken that nosotros freaked out."

One of the scariest things that happened to me, happened on Sunday night. I slowed down [my car] very nicely and here come these ii little National Guard boys. One goes, "Why are you out?" I tell him I'm a reporter, and he has something smart to say. 'Cause I don't recall he had seen likewise many [black journalists]. . . he's from the wilds of Baltimore County.

He wants my identification. I have to get [gestures reaching into her back pocket to retrieve ID]. When I did this, he jammed the bayonet in the window. Scared the absolute [crap] out of me. In retrospect, you tin can see how people get shot so fast.

I never did tell my mother that. And I'm stupid plenty to get irate. I also know he didn't have whatsoever bullets, wasn't supposed to take whatsoever bullets, anyway. So I told him, "Get that goddamned [thing] out of my face, I'1000 getting you lot identification." I call up we were both scared of each other."

Jewell Chambers' interview—edited for length and clarity—took place in 2008 as part of the University of Baltimore'due south "Baltimore '68: Riots and Rebirth" project.

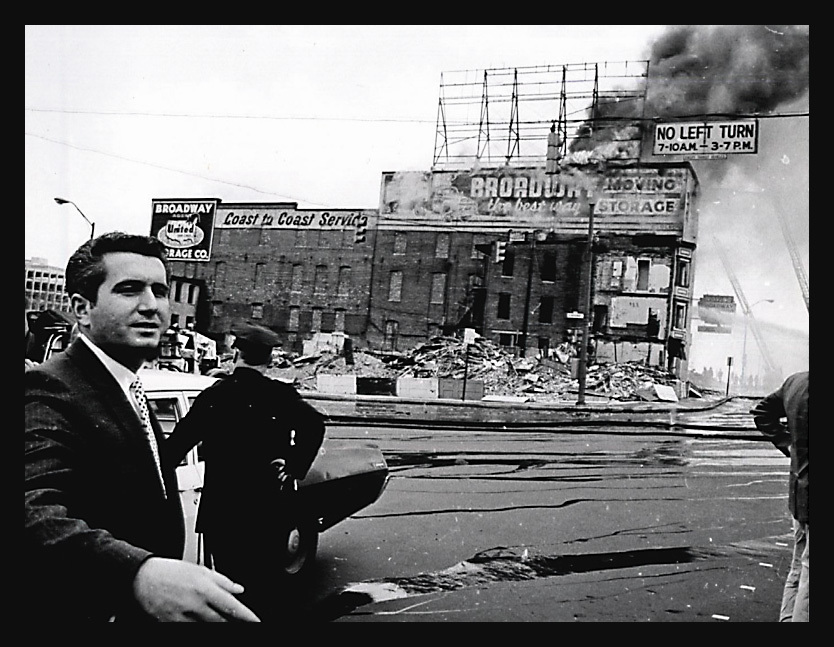

Mayor Thomas D'Alesandro III surveying the damage during the 1968 riots.

Robert Embry Jr.

Urban center Councilman

I represented the 3rd District, which was and then Northeast Baltimore, an overwhelmingly white commune at the fourth dimension of the riot. They talked to me well-nigh their fears of unhappy African Americans coming out from the city to wreak havoc on their neighborhoods. It was based on zero, just that'due south what was happening. I was only a city councilman for six or seven months. I put in an ordinance to create the Department of Housing and then, in July, Mayor Tommy D'Alesandro appointed me commissioner. I had been elected in 1966, defeating John Pica, who was a spokesman for white backlash. On the City Quango, I believe, there were iv African Americans out of 18 members—19 with the City Council president.

D'Alesandro, pictured below, was elected in part on a platform of building more schools in African-American neighborhoods and utilizing the War on Poverty programs of LBJ.

So-chosen "blockbusting" was in full swing in the Northwood and Edmondson Village neighborhoods, and that was a big effect. Essentially, a existent estate agent would distribute pamphlets in white, borderline neighborhoods saying that an African-American family had bought a house nearby, causing white people to become agape and sell their house at a steep discount. The real estate agent then turned around and sold the firm at an inflated cost to a black family unit, exacerbating the turnover in population. Neighborhoods became compatible.

There was also a corking deal of antagonism about urban renewal efforts in Bolton Colina, Camden Yards, and around Johns Hopkins and the University of Maryland. They were targeted toward slum housing, but there weren't any benefits going toward people who were displaced.

I had been involved with Core and the NAACP, and I had campaigned for open housing laws. I demonstrated in front end of the Northwood Theatre [which had refused to integrate]. I knew the history of race in his land. The suppression. I never asked anyone about the causes of the riot. Information technology seemed self-evident.

The metropolis is a complicated thing. But the main problems remain, namely poverty in many neighborhoods. One change is that the philanthropic community that exists today didn't exist. Philanthropy at the time just meant funding private schools, the symphony, and art museums. There weren't whatsoever of the foundations that have grown upward since trying to relieve the inequalities. The French republic-Merrick Foundation, Open Society Institute, Aaron and Lillie Straus Foundation, Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foundation, Blaustein Foundation, Annie E. Casey. We [Abell Foundation] are xxx years old.

The Goldseker Foundation was the first, in 1975, which is interesting. He [Morris Goldseker] was someone who served as the personification of a slumlord and blockbuster for many people. —Robert Embry Jr. is president of The Abell Foundation.

Rev. Marion Bascom

Pastor

There was so much hope, and information technology was shattered by the untimely death of Martin Luther King, and the town went crazy. Not only Baltimore, but almost every metropolis in the land experienced the same matter. Information technology was nigh equally if blacks in every community had suddenly been inoculated with a hypodermic needle and caught the disease of disturbance. And so they began to fix fires, and it was only horrible. You could smell smoke anywhere in Baltimore City.

[After things settled downwardly], Agnew called many black leaders downtown to his President Street office, and he began to berate the colored, Negro, black community for their backing up and not protesting other blacks who were running rampant in the streets. Governor Agnew said, "When the trouble came, you leaders ran." And he began to berate those of united states who were there. There must have been at least 50 of united states [that] got up and started walking out. We came up to our church [Douglass Memorial] to discuss what sort of action we would take.

Well, life for usa later the disturbances is withal trying to learn [from] each other every bit human beings. I of the tragedies, I think . . . lies in the fact that American society has developed around racial consciousness. So that even to this 24-hour interval, when I go into an establishment that is white-owned and operated, I have the feeling that someone is sort of watching me. I think all blacks are sensitive of information technology, of that same feeling, so that we have developed a society where, unconsciously, we are not able to react to others as human being beings.

—Bascom's interview—edited for length and clarity—took place in 2006 every bit part of the University of Baltimore's "Baltimore '68: Riots and Rebirth" project.

Milton Dugger Jr.

Singer

In 1968, I was with the Chaumonts, a pop and rhythm and dejection band. I was the singer. Nosotros were playing in the Harrisburg expanse the weekend after Martin Luther Male monarch was shot. That was a Th. One of the days the World stood still. And then we didn't know anything that was going on in Baltimore. We were driving downward York Road from Towson after the task when we came upon the National Guard. That was disconcerting.

I grew up in Upton. The side by side twenty-four hour period, I rode around and observed a lot of cars with out-of-state plates—P.A., New Jersey, and Virginia—and groups jumping out of cars. Pennsylvania Avenue was destroyed. I'grand one of those people who don't recollect this was only Baltimore folks. The place where my family unit shopped—our corner shop—got hit. The riots brought an terminate to a lot of corner stores. Jewish folks felt betrayed. Non ever so much over the looting, but the burning out.

People who are disenfranchised don't know who, or what, to strike out confronting, and they began doing stupid things. They weren't protesting Dr. King's assassination past destroying something in their own neighborhood. They were just angry and upset.

I spent virtually ix years teaching English language in Baltimore City public schools, and my students at Clifton Park Junior High Schoolhouse were very depressed afterwards and I was concerned nearly them. It felt like a crucifixion. How tin this be? You tried to at-home the young people downward, only there was a lot of crying. At the same time, you lot had to calm yourself downwardly. The staff, the faculty, the administration was very upset, and they were crying, as well.

Ralph Moore

High School educatee

I lived in Sandtown and took iii buses to get to Loyola Blakefield High School. During the riots, I literally had to run by tanks and National Guardsmen with stock-still bayonets to make it home before half-dozen p.m. and so I wouldn't become arrested.

I had dozed off on the couch and remember my male parent waking me up to tell me Martin Luther Rex had been shot. When things exploded, I remember staying up all night with my mother looking out the window. The police were almost in a frenzy trying to proceed the chapeau on things. From our house, you could look downwardly Bullpen Street and see people breaking into the stores on Pennsylvania Avenue. I don't recollect things feeling immediately bleak afterward, merely a lot of merchants never came back.

Loyola was a different world. The Jesuits had wanted more multifariousness, and myself and three other guys had received $ane,600, four-year scholarships. King'due south bump-off was a big marker for u.s.. We started wearing Afros. In 1969, we formed a black student union. We fought to have African-American literature included in the curriculum. But [my feel at] Loyola was a mixed purse. The racism could be subtle or overt, and information technology came from the adults, non our classmates.

Subsequently I graduated college from Hopkins, I taught at Loyola for two years. I however remember walking into a football game game with a couple other white faculty and getting stopped and singled out by a parent volunteer who didn't believe I taught at the school.

PAUL COATES

Time to come Black Panther leader

I was not an activist in 1968. I was 21, merely out of the military afterwards 19 months in Vietnam. I was living with my wife and daughter in Blood-red Hill.

I remember thinking Baltimore would not riot. I am from Philadelphia, and Baltimore did not seem like a New York or Los Angeles in terms of its militancy. Baltimore was—still is—a strange place. People are quieter. It'southward the Southern influence. I just didn't call up the response to Southern-style oppression was going to exist violent here.

For many people, Martin Luther King was someone who delivered hope. Malcolm X had already been killed, and what do you when your leaders are assaulted? At first, I thought Martin Luther King's expiry might serve as the basis for a war in America. Not necessarily a race war, but war is what it looked like when yous saw the fires and rioting breaking out across the country and the U.S. Army and National Guard getting called in.

It would have been hard very to grow up in this country and non sympathise that there was a social disharmonize going on, twisting around race. Merely I was not "woke," as they say today. I was nevertheless asking questions. King's assassination and the riots were part of that awakening procedure, cartoon it all into a sharper perspective. Watching people on TV in the South being attacked past police dogs during peaceful protests had been office of that process; Emmett Till had been part of that process. At that place were 1,000 things and it took a thousand more. I started looking for more data, looking for other people who were also "woke." A year later, I volunteered with the Blackness Panthers.

Reflecting dorsum, even as I say "riot," in that location is a modify in perspective. I see it as resistance to a long, steady stream of abuse. People responded in a destructive way, and most of Baltimore idea they were crazy. Just these people rioting in the street did non know what else do to. They were not being heard.

—For the past 40 years, Paul Coates has been the publisher of Black Classic Press in Baltimore. He is the father of National Book Award winner Ta-Nehisi Coates.

Sharon Pats Vocalist

Daughter of pharmacy owners

The [800 block of West] North Avenue was a white area when my parents bought the chemist's in 1950. We lived upstairs, and my brother was born in 1950. I was born in '51. All nosotros knew was Northward Avenue. That was our home. And then, as the years went on, the neighborhood did modify and it became a mixed neighborhood. The store was a multipurpose kind of place. The customers, most of them were regular customers. My mother really was the proprietor, and my father was the chemist. Their life revolved around the shop.

We would come abode from school and go to work in the store. I would be downwardly there and waiting on customers and talking to people, and it was great. I enjoyed it. I went to Western [High Schoolhouse] in the metropolis. At that time it was downward on Howard and Center Street. I would accept the bus.

When the riots came, I don't remember that nosotros idea anything bad was going to happen. It was a trusting kind of thing where this was our neighborhood, and it just wouldn't happen, they just wouldn't practice this, and it never occurred to us.

So, that Sunday morning, we went shopping. I took the car, and [afterward] I was going to pick up my sis, Betty [at Hebrew School].

"And the whole cake was in fume and flames. That was the point that we freaked out."

I came down 83, I'm 16 and I take this big auto and I'grand driving. We turn off on the get out, which is North Avenue, and make a right to get towards the firm—you could run into the neighborhood—it's a couple blocks upwards, right nigh Mt. Majestic. And the whole block was in fume and flames. That was the point that nosotros freaked out. Now, we didn't know what was going on. My father was sleeping because it was Sunday morning, and nosotros were like, "Oh my God! Is he okay?"

All I saw were masses of blackness people in the street. And flames. And they wouldn't permit the states get past, so I knew the back roads, and went around and came down to the Esso station, which was there beyond the street. There was my father, waiting for united states, standing in the Esso station. I will never forget that. He got in the car, and nosotros left. We picked up the Eisenbergs. They had no auto. The Eisenbergs had the jewelry repair shop two doors downwardly. We went to my aunt's house. And that was the end of my life as I knew it.

—Sharon Pats Singer's interview—edited for length and clarity—took place in 2007 as role of the University of Baltimore's "Baltimore '68: Riots and Rebirth" oral history project.

Bernard took the pb outside, wielding a chainsaw to cut back overgrown shrubbery and plotting the eight garden beds on the eastward side of the business firm. The lake-facing side of the firm is at present centered around the two-story bay window.

Kalman R. (Buzzy) Hettleman

Assistant to Mayor Thomas D'Alesandro III

Everyone hoped naught would happen. But nobody was surprised [in the mayor'due south office]. Tommy was suspect initially in the African-American community considering he was of the old Democratic institution, merely he was a very liberal mayor for the fourth dimension. He brought African Americans into loftier offices in the city for the showtime time. He appointed George Russell to Metropolis Solicitor. Rev. Marion Bascom to the board of burn commissioners. Appointed Jim Griffin and Larry Gibson to the school board.

I remember the sense of helplessness riding around the city and seeing the fires.

I remember meeting with all the merchants at the Mechanic Theatre, who were outraged about all the stores that had been burned down.

As a white person, I'd have been hard pressed to fully empathize with the black community and understand what was happening and why. To use today's term, information technology simply went viral in the street. Information technology was a thing of long-simmering discontent. Martin Luther King's murder was the catalyst.

We were trying to do information technology all—improve schools, housing, community development, policing. Drugs weren't a big event, but policing was. [Donald] Pomerleau was the commissioner, and he was a controversial effigy. Gruff. The mayor was nether swell pressure to engage an African-American police commissioner [which didn't happen until 1984 with Bishop Robinson].

I don't recall in that location were any abrupt policy changes after. Tommy had been welcoming to the problems the African-American community raised before the riot. There was flight. People were going to the suburbs. That was a business.

I do call back we had more hope in the 1960s that we were going to make a difference.

Source: https://www.baltimoremagazine.com/section/historypolitics/when-baltimore-burned/

0 Response to "what happened to esso building 7720 york road towson md"

Post a Comment